If we’re talking about impacts of school choice, let’s look at real examples – More on Kentucky and Florida

Back on March 1, 2021 I posted a blog about “If we’re talking about impacts of school choice, let’s look at real examples, not guesses.” That blog looks at how public schools in school-choice-rich Florida and school-choice-devoid Kentucky performed on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the early days of the Kentucky Education Reform Act of 1990 and how both states perform now since Florida enacted a rich cornucopia of parental school choice programs while Kentucky still essentially has none.

That first blog examined trends for Florida from the NAEP averaged across all public school students from the first year of reported state test data and the most recent results from 2019 for math and reading in both the fourth and eighth grades.

The results were quite revealing, especially in the fourth grade, where Florida clearly came from well behind to surpass Kentucky.

The earlier blog also examined several possible explanations for why Florida moved ahead.

One possible explanation was funding changes in the two states. However, it turns out that Kentucky actually moved from behind Florida for public school per pupil funding in the early 1990s to spending notably more per student as of the latest available information for 2018. If anything, Kentucky should have done better than Florida, not the reverse.

The first blog also examined student demographic shifts between the early 1990s and 2019. Because of the unfortunate truth that minority students don’t score as well as white students on the NAEP, a shift in demographics could explain relative score changes. But, Florida had bigger shifts towards minority student enrollment than Kentucky did, so that explanation doesn’t fit with what actually happened, either.

The only other major difference I am aware of between the two states is the dramatically different amount of school choice now found in Florida versus Kentucky. It seems likely that choice has played a major role in Florida’s public school progress on NAEP.

Now, that first analysis covered only the overall average public school student scores for each state on the NAEP. As regular readers know, NAEP report cards recommend looking deeper, so I did that by breaking out scores only for black students in the states that had scores reported for this racial group. The result is this new set of NAEP comparison maps for Grade 4 and Grade 8 public school black student scores in reading and math.

As you can see in the first graphic, Florida moved from having 20 states statistically significantly outscoring it for black student NAEP Grade 4 Reading in 1992 to where no state now outscores it. Wow! Along the way, Florida’s black students moved from scoring statistically significantly behind Kentucky to scoring statistically significantly ahead. Double Wow!

And, don’t forget, Florida moved from spending notably more per student in 1992 to now spending notably less per the most recent data available.

Here is the picture for Grade 4 math for black students in public schools.

The Grade 4 reading situation is pretty much replicated, even to the point of Kentucky moving from statistically significantly ahead to statistically significantly behind Florida. Wow once more!

The picture for the eighth grade isn’t as dramatic, but here are the maps.

Notice that for Grade 8 NAEP reading testing didn’t start at the state level until 1998. Perhaps the Florida picture would look more dramatic if we had earlier NAEP data to examine.

Still, Florida made some progress and no longer does any state outscore it for Grade 8 NAEP reading for public school black students.

Finally, here is the picture for Grade 8 public school black math in NAEP between 1990, the first year this state test was administered and the most recent 2019 results.

On the Grade 8 Math NAEP, note that Florida moved from behind to now statistically tie Kentucky for black student results. And, again, Florida did that while slipping from spending relatively more to relatively less than Kentucky, too.

So, if the school choice programs in Florida don’t explain these changes, what does? No one has offered an alternative answer, so it looks like choice is pretty likely to be the reason why Florida has made such dramatic improvement on NAEP for its public schools. Choice creates competition that motivates.

By the way, some folks on Twitter are really upset about these facts coming to light. They have been trying like mad to discredit the earlier blog, sometimes saying some pretty outrageous and clearly incorrect things like claiming I provide no analysis on the earlier blog (just read it again – that is false).

Some of the critics also pushed a silly claim I am a racist just because I point out the unfortunate fact that there are achievement gaps on the NAEP and that means the performance by race needs to be considered as a possible explanation behind score changes. Those critics should know a lot of experts at the NAEP agree with me.

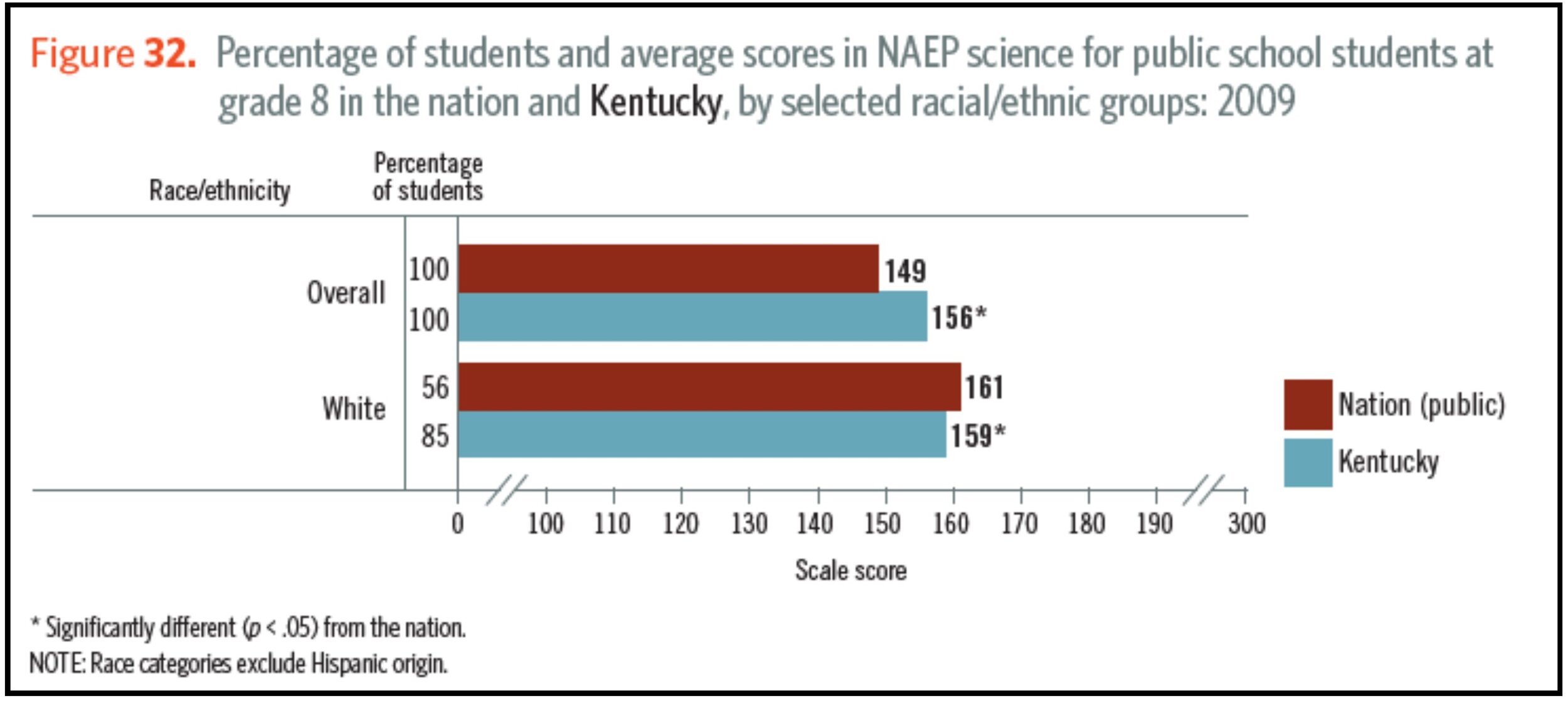

In fact, if you look at the NAEP 2009 Science Report Card, on Page 32 it specifically discusses how the picture from NAEP can change dramatically once you factor in consideration for different racial groups. The figure below, which is Figure 32 in that 2009 NAEP Science Report Card, actually uses Kentucky’s NAEP performance as an example to show how the picture from NAEP can change rather notably when the data is disaggregated and considered by race.

When we look at overall all student scores, Kentucky scores statistically significantly above the national average. But, when we look only a white student scores, Kentucky scores statistically significantly below the national average for whites. That’s a really different picture.

The same page in the 2009 Science Report Card has another example that cites Florida’s Hispanic performance.

If we only look at overall performance on NAEP Grade 8 Science in 2009, we would say Florida was still behind. But, once the data is disaggregated, Florida’s Hispanic students score statistically significantly higher than the national average for their racial counterparts in other states. You have to disaggregate the data too see all of this. It isn’t racist. It’s just good analysis.

Note: Kentucky didn’t have enough Hispanic students to get NAEP scores in the early days of state NAEP testing, so I cannot look at those changes over time in the same way that I did for overall scores and now for black student scores.

So, racially insensitive critics might not like it, but even the NAEP’s own documentation shows the folks at the National Assessment Governing Panel and the National Center for Education Statistics, who collectively manage the NAEP, obviously agree that student demographics can be a critical factor that needs to be considered in NAEP analysis. I was doing what experts recommend.

Unfortunately, attempts to suppress discussion of achievement gaps might be driven by a reprehensible desire by some in the K to 12 community to try to hide the fact that major public school achievement gaps still exist today. Those gaps show on the NAEP just like on most other evaluations of public school performance.

Note: One exception: some public charter school results, such as those reported here, led the Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education in Massachusetts to ask:

“What is it about Charter Schools that allows them to achieve such strong results?”

So, forget those folks who are trying to deflect from the important message here. Unless someone comes up with another reasonable explanation – so far notably absent – for how Florida with lots of school choice outperforms Kentucky with virtually none, and does so while spending notably less, I’ll stick with the idea that school choice causes competition in Florida that improves its public schools, too. And, Kentucky could use a lot more of what Florida now has.