Important student proficiency rate gaps widen in new Unbridled Learning results

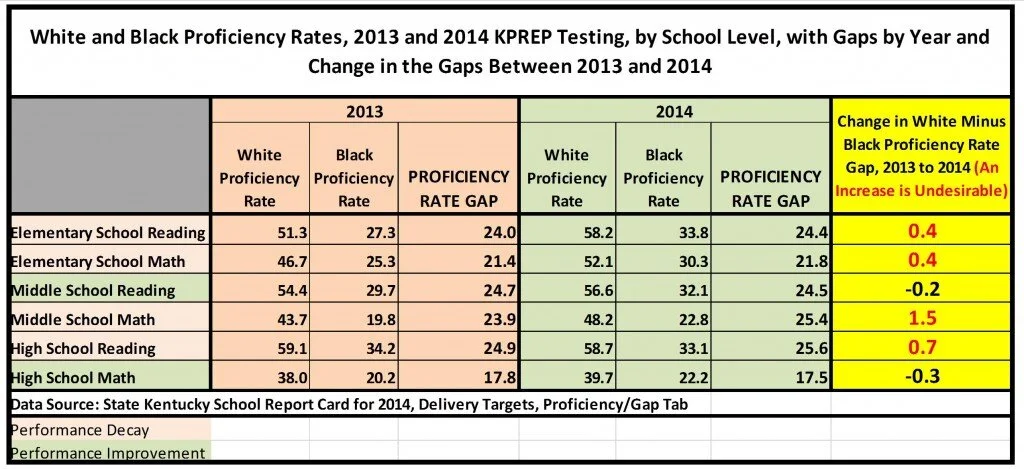

The new Unbridled Learning results contain some generally unhappy news about chronically problematic gaps in reading and mathematics proficiency rates between Kentucky’s white and African-American students. The table below, which captures the last two years of proficiency rate data for whites and blacks from the Kentucky Performance Rating for Educational Progress’ (KPREP) Common Core aligned reading and mathematics tests, tells the story.

In four out of six cases, the white minus black proficiency rate gaps edged up (got worse) between 2013 and 2014 as shown in the yellow shaded column on the far right.

There was scant improvement only in the Middle School Reading and High School Math areas, but the changes are so small that they have to be considered essentially flat.

Thus, while black proficiency rates did improve a little in most subject/grade combinations listed in the table (though high school reading actually dropped), the improvement was not as good for children of color as it was for Kentucky’s whites.

Furthermore, the latest KPREP black proficiency rates in 2014 indicate only about one in three, and sometimes closer to just one in four, black students in Kentucky are meeting proficiency targets.

It is important to understand that the Unbridled Learning “Gap Group” calculations cannot and do not show this problem. That is because the “Gap Group” calculation in Unbridled Learning lumps all special student groups – the minorities, learning disabled, English language learners and the poor – together as one group of students and then only calculates the overall average proficiency rate for this group.

There is no comparison to progress for white students with the Gap Group calculation.

Furthermore, due to the averaging process and the large number of poor whites in Kentucky’s schools, in most cases the Gap Group results are mostly just results for poor whites in Kentucky’s school system. The other special student groups get lost in the averaging.

The table above provides more evidence that Kentucky’s school children, especially the minority kids, need better options, such as charter schools. So far, after nearly a quarter of a century of Kentucky education reforms, the regular education program still does not meet their needs.