No, high poverty doesn’t always lead to poorer school performance, especially for minorities

The new, 2018-19 school year public school accountability report is finally out for Kentucky. Overall, as the Courier Journal points out in “New Kentucky test scores show stark differences in JCPS schools’ achievement,” the results are “underwhelming,” at best. We’ve already looked at predominantly falling performance on the state’s KPREP tests and on the ACT college entrance test, but it’s time to provide some counter arguments to doom and gloom crowd who keep saying schools can’t get better unless we fix poverty, first.

Well, there is indication in the new testing data that some schools are breaking the mold even though they have some really high poverty issues.

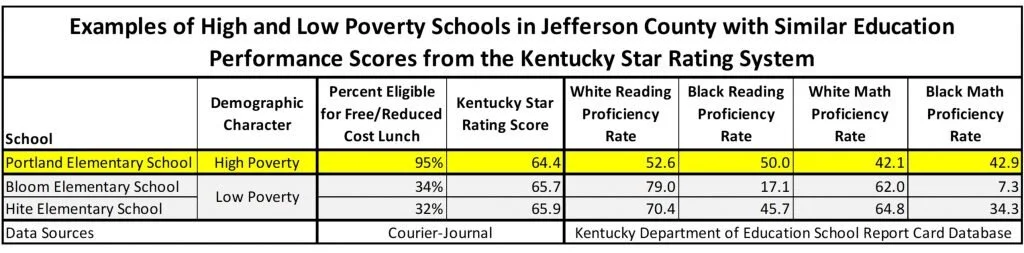

One example is from Jefferson County, and I discovered this while looking at the first graph in that same online Courier Journal article. In that Courier graph, if you move your cursor over the various dots, the specific data for the school represented by that dot pops up. Using that graph, I collected the “Percent Eligible for Free/Reduced Cost Lunch” and “Kentucky Star Rating Score” data for the three schools shown below. I then added more testing information that came directly from the Assessment and Accountability, Accountability Proficiency, By Level, section in the new school report card database from the Kentucky Department of Education.

As you can see, the first school in the table, Portland Elementary School, has an extremely high student poverty rate as exemplified by its students’ 95% eligibility for the federal school lunch program.

The two other listed schools, in sharp contrast, have far lower school lunch eligibility rates, generally about only one-third the size of Portland’s rate. That’s a real poverty difference.

Never the less, when you examine the scores for each school in the Kentucky Star Rating Score column, all three schools have very similar overall accountability scores under Kentucky’s new school rating system. That by itself is rather remarkable.

Still, the new star rating system might not be getting everything right, so I also pulled up each school’s 2018-19 proficiency rates for whites and blacks in math and reading.

The story here for white students is more in line with what might be expected. The rich schools do notably better than Portland for white students.

But, take a look at the story for black students in these three schools. Portland, despite its astonishingly high poverty rate, does a lot better for black students than either of the rich schools.

I also extracted the statewide average black elementary school proficiency rates for reading (31.1%) and math (25.5%) from the new report. Clearly, ultra-high poverty Portland beat both those statewide averages by a notable amount.

So, it seems that we shouldn’t be settling for the sorts of results that Bloom gets with black students.

By the way, both Portland and Bloom wound up with the same, 3-Star rating overall. Neither school wound up in either the CSI or ATSI troubled school categories.

However, with Bloom’s dismal black reading proficiency rate of just 17.1% and the truly deplorable math proficiency rate of only 7.3%, that somehow seems wrong. In fact, among the 257 Kentucky elementary schools that had math scores reported for their black students, Bloom ranks way down near the bottom at number 244.

Clearly, at least for black students, Bloom is really problematic. But, the overall report classifications don’t tell us that.

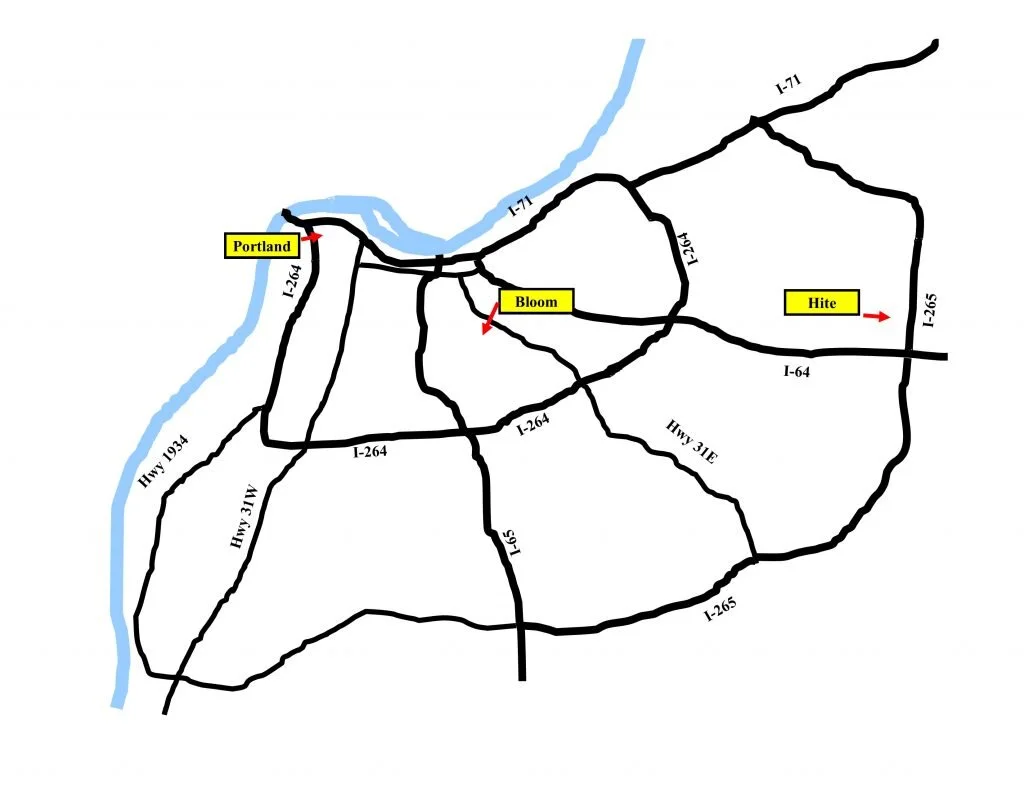

There is a geographic element to this, too.

Those familiar with my Blacks Falling Through Gaps in Jefferson County series (see the most recent edition here) know that schools with the biggest white minus black achievement gaps in Jefferson County schools tend to be found in the upper-scale, east side of the district, generally east of I-65. I plotted out the locations of Portland, which is in the solidly high-poverty West End, and Bloom and Hite. Once again, the trend of better performance for black students belongs to what is supposed to be the lower-performing West End. Black students in Bloom and Hite might be better off not to bus over to those schools.

To close this out, the work in Portland is far from complete. But, the message here is that more is possible than we see in other schools, and I sure hope the senior education leaders in Jefferson County – and the rest of the state, too, for that matter – are paying attention.