Comments on the Charter School Debate: Charter failure sometimes expected

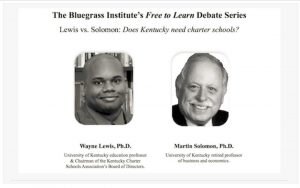

If you have not taken time to read our major charter school debate with UK professors Wayne Lewis and Martin Solomon, you owe it to yourself and Kentucky’s children to take some time to do so. The professors provide a good introduction into the issues of establishing charter schools in Kentucky from the viewpoint of both a strong proponent of charters and a sharp critic of these school choice options for parents.

Now that the professors have weighed in, I’m adding more to the discussion. I already posted several blogs on the fact that charter schools are public – NOT private – schools and, at least in states with the kind of solid charter school laws we’d like to see in Kentucky, they are highly accountable.

I also talked a bit about the fact that some charter schools have failed. There are a variety of reasons why, but one that didn’t get mentioned in the debate is important to understand. When charter schools started, one of the goals was to use them as a sort of education laboratory to finally learn some solid things about what really does work for students. Such research was badly needed, and it still is today. But, whenever we do research, we have to accept the reality that some things just don’t work out.

Let me expand on that. The vast majority of research in education is pretty poorly done stuff. Arthur Levine, the past president of the Columbia Teachers College in New York City has written eloquently about this topic in his “Educating School Teachers” and “Educating Researchers” reports.

For example, in Educating Researchers, Levine wrote in 2007:

“One question encompasses all of these areas of concern: After a quarter-century of a national school reform movement in which scores and scores of improvement initiatives have been attempted, what works in raising student achievement?” (Page 13)

Levine answers his own question:

“The answers to these questions have not been forthcoming. As a result, education policy in America has become a matter of ideology. The right, the left and single-interest groups are locked in a white-hot, self-righteous battle over the directions our schools need to take. There has been little rigorous research to produce empirical evidence in support of any position (emphasis added).” (Page 13)

With decent research and evidence lacking, charter schools often have to blaze their own trails as they start down the road to developing education programs that work for kids, not ideologists.

To be sure, some charter school activities, such as hiring staff to teach who didn’t come out of education schools, have been pretty radical, at least by normal public school standards. Just as with any research, some of those charter efforts simply didn’t work out (though there have been good reports about those non-credentialed teachers).

My point is that some failures don’t mean that the charter school program overall is a bust – clearly it isn’t. But, given the lousy research starting point charters had to deal with, some attrition was inevitable.

It is important to understand that with the quality of education research remaining in doubt, charter schools still offer one of the better hopes for us to discover what really does work for students.

Furthermore, unlike the situation in traditional public schools, which sometimes subject students to education programs – sometimes outright experiments – that parents don’t want, no-one forces a parent to send a child to a charter school. If a parent prefers their child not participate in an experiment in a charter school, the parent, not the school system, has that choice. This makes charters a solid way to conduct research programs, far more suitable than the traditional school system can ever be, and something still badly needed as education research too often continues to be, as Levine points out, mostly “a matter of ideology.”